Is a Yuan devaluation around the corner?

And what that implies for us in India?

The Chinese equity indices have been bleeding for sometime. There has been no shortage of “buy” recommendations and the occasional news of potential interventions by the authorities. And yet, the slow bleed continues.

(Chart below has the China A shares and China H shares indices)

This begs the question whether something more needs to be considered here? A good starting point could be the currency i.e. the Yuan

But the Yuan is no simple currency

It was officially pegged to the USD to facilitate the growth of the Chinese manufacturing engine. As the success story built, pressure mounted to de-peg the Yuan and let it appreciate to reflect the strength of the Chinese economy. This led the authorities to re-peg it to a “basket” of currencies - effectively creating a “controlled” currency v/s a pegged currency.

But this was while the US & China were officially friends.

The superpower rivalry today is across domains - military, industrial, sports, technology, AI, energy transition etc. However, the most crucial domain is currency. In most fields, China maybe at par or even ahead of the US, but it lags by a country mile in the use of Yuan in global trade & markets v/s the use of the USD - the global reserve currency.

China being a capital controlled country puts limits on the use of Yuan as a global reserve, but its use in trade settlements has grown post Covid.

If China truly desires superpower status - global usage of the Yuan is a precursor.

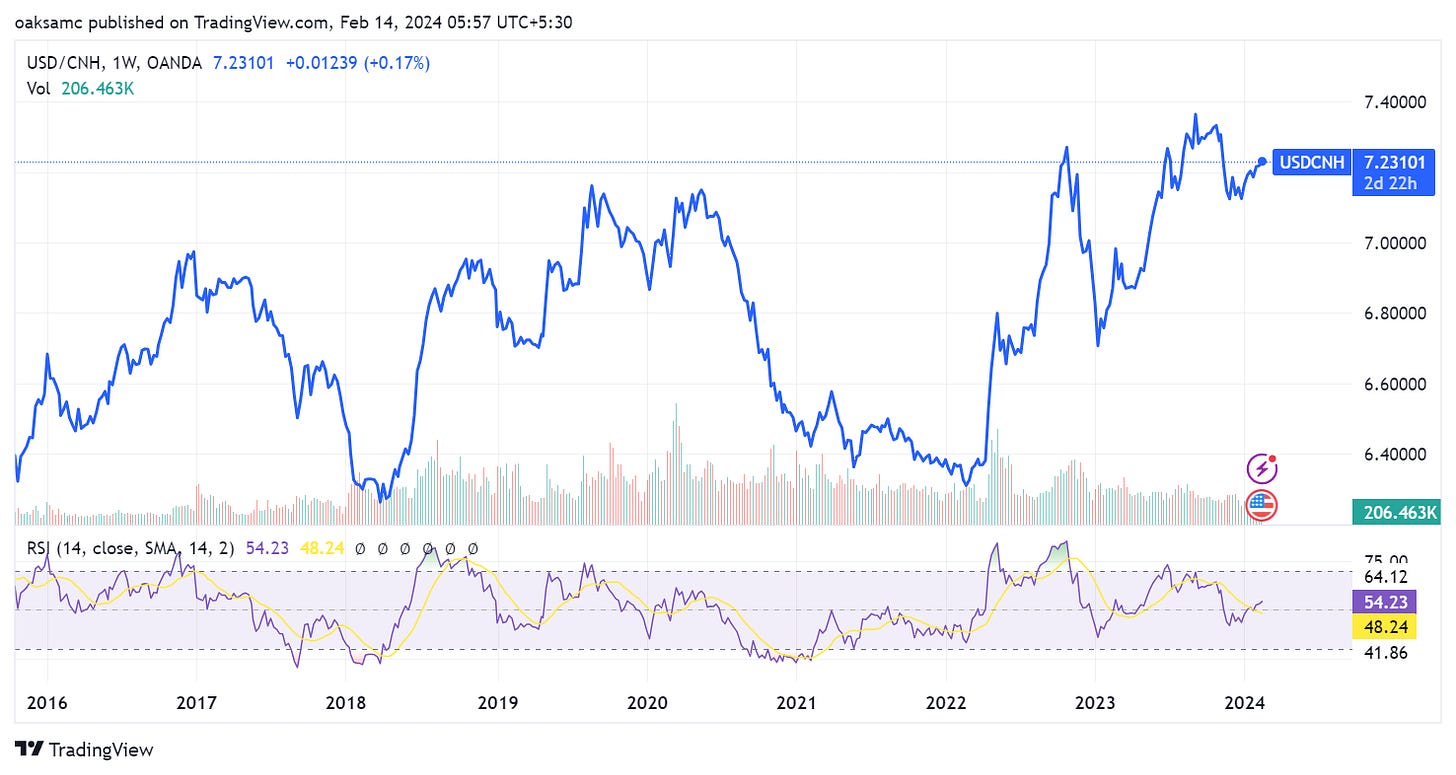

The price action of the Yuan is reflective of the weakness in the economy. All this while the narrative of China + 1 has built up and seeing some action as well with Mexico and Vietnam emerging as new manufacturing alternatives.

It is debatable how much the relocation of manufacturing to these countries hurts China. Firstly its more low end manufacturing, and China’s more affluent population likely cares less about those jobs. Secondly many of the manufacturing units in Mexico and Vietnam may well be China backed.

But it maybe a different story when it comes to high end manufacturing i.e. the are for future jobs - and that's where Japan - the oldest enemy poses a new challenge.

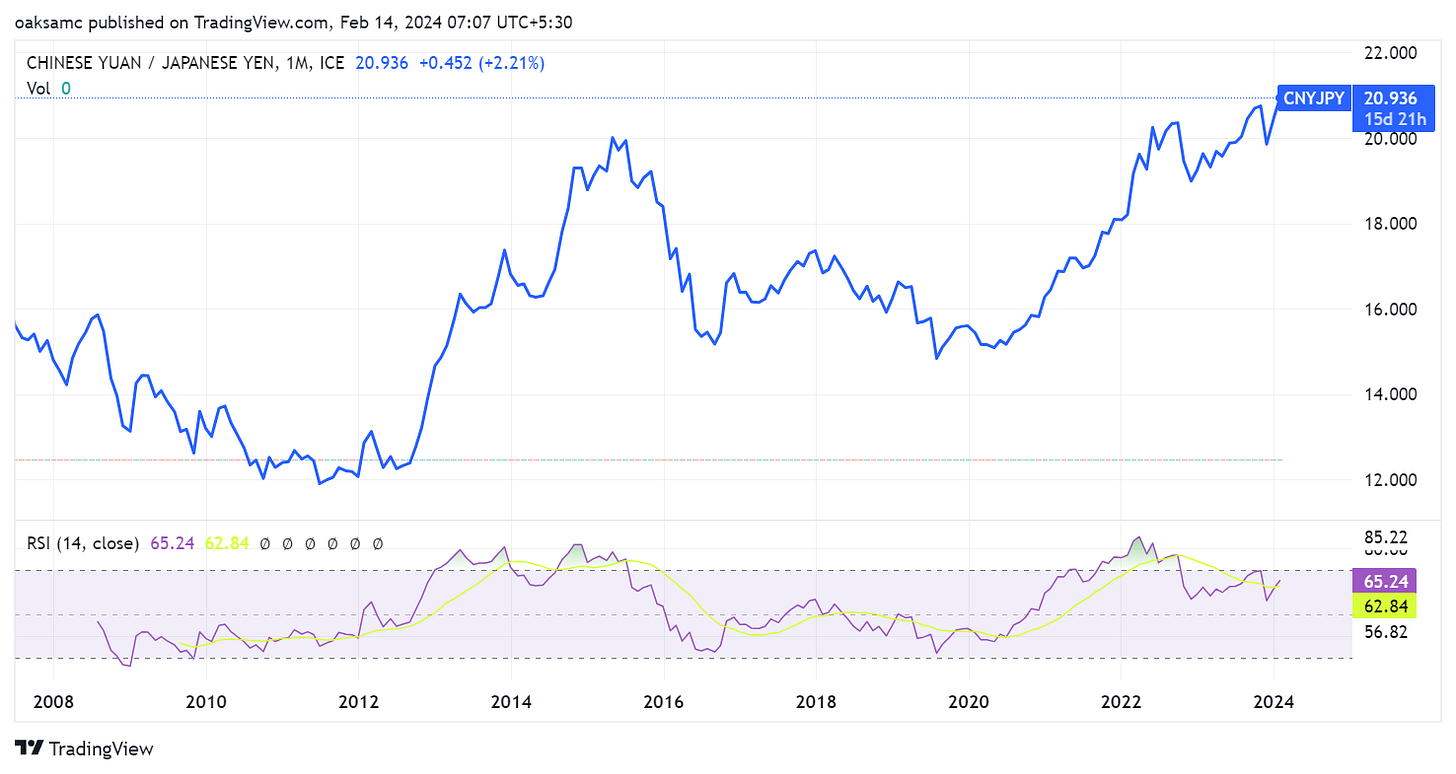

Since Abenomics came into force in 2012, Japan reversed its Yen appreciation policy to make it more competitive on exports, bring back some inflation and exit from the deflationary spiral it has been in since the late 80s.

This Yen depreciation accelerated post Covid & the Ukraine war - incidents which likely changed the global macro regime to one of “Wartime economics”.

The Yen depreciation is a way for the West to wage a financial and economic war on China.

The impact of this on China is seen in the CNYJPY chart where the Yen has already hit new lows against the Yuan. Since Abenomics began, the Yen has depreciated to half its value - a big boost for anyone looking to relocate high end manufacturing supply chains.

But the Yen depreciation has a lot of knock on effects on global markets - the biggest of which can be seen in global bond and currency markets.

It forces competitive devaluation by other exporters like Germany and Korea, thereby weakening the Euro and the Asian currency basket.

Rising costs of hedging the Yuan reduces Japanese buyers of US bonds causes USTs to fall, pushing up yields and tightening financial conditions. See the close correlation in the chart below of the JPY with US govt. bond yields.

So what could be changing in China?

The fall in the Yen is not new, albeit it has accelerated post Covid. Yet, China held off on any attempts to depreciate the Yuan to respond to this currency war. A potential reason for that may have been the large USD bond issuances by Chinese firms especially the financials in the past decade. Devaluing the Yuan would have caused those bonds to go belly up, and shut access to USD bond funding for Chinese firms.

Much of this funding may well have been getting recycled into real estate. Chinese real estate stocks have been correcting since 2018 (see below) - which suggests the real estate woes are not new.

But something maybe changing -

The defaults by large firms, which started last year, suggest that the cover from policy makers for real estate and related non bank financing is moving, and hence protecting bond investors maybe less of a concern.

If news reports are to be believed, a policy shift favoring manufacturing over real estate is underway. It would seem the appropriate response to the China + 1 and supply chain reset narrative globally. More Semiconductors, Less Housing: China’s New Economic Plan

Softer oil and gas prices put less of a strain on China’s energy needs and its rapidly growing EV industry may mean less future oil demand.

Such a scenario may make conditions more amenable to a Yuan Devaluation and regain the competitive edge - i.e. a Chinese version of Abenomics.

And how would this impact India?

India has also staked its claim in taking a share of the global supply chain reset and put itself on the path to becoming a key manufacturing destination, However, till that policy objective of China + 1 (many) is achieved, we may have little choice but to have the INR be competitive with the CNY.

As the CNYINR chart suggests, this isn’t altogether a new policy. It has been in play already since 2014, albeit post 2020 saw a rebasing to a weaker INR.

Should the Yuan devalue as the policy incentives for China changes, to retain competitiveness, the INR may also need to devalue.

And what does that portend to Indian equity markets

INR hedging costs have been at 1.5% - 2% in the past 2 years, well below historical averages of 3.5% - 4%. A sympathetic depreciation of the INR in response to a CNY devaluation would cause the hedging costs to rise.

This has a direct impact on bond yield spreads for Indian bonds, which could potentially re-price equity valuations in line with lower bond valuations.

We wrote about this scenario - Pricing potential currency depreciation

Now that might be a happy outcome for bond investors who need to follow global bond indices where Indian bonds make an inclusion this year!

It maybe less rosy for Indian equity investors in the near to mid term.